It would be easy to say that I've been struggling to find the "right" words these days, but words are a crucial part of the work that I do, even if many of them happen behind the scenes. Three plus months into this - whatever this is - has shown that actions are more impactful than words, too. And sometimes images help move the tide of discomfort and reckoning along as well.

|

Last night, we had a pretty remarkable sunset - not so unusual, but this time I thought to pick up my phone and document the sequence of images. Scroll through the images above to see the best three.

It would be easy to say that I've been struggling to find the "right" words these days, but words are a crucial part of the work that I do, even if many of them happen behind the scenes. Three plus months into this - whatever this is - has shown that actions are more impactful than words, too. And sometimes images help move the tide of discomfort and reckoning along as well.

1 Comment

Today marks two months since the last time I was in the office, which is nearly even with the amount of time that I spent in the office from January to mid-March, settling into my new job.

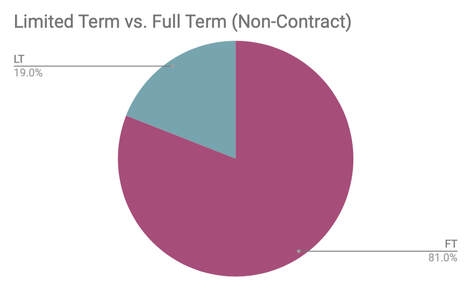

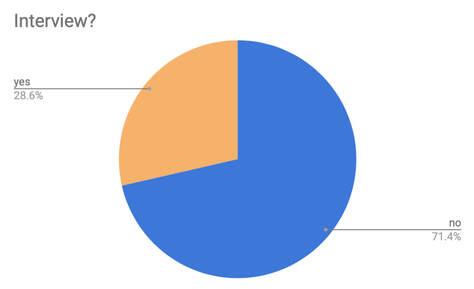

Working from home has both its challenges and its benefits. One of the latter is the opportunity to take morning and evening walks each day. Yesterday, before settling into work, I randomly went on a route opposite from my usual direction. And lo and behold, on a bridge close to home, I found the baby hawks I had read about a few days prior. The trio of red-shouldered hawks is nesting just off a bridge, high up in the trees from the Klingle Valley but at eye level with bridge passersby. I actually saw mom or dad flying last weekend while on another walk, but didn't know that there were babies (or eyases, as they are technically known), until recently. I've discovered that they have their own twitter account; their names are Cleveland, Covid, and Dorothy; and their dad recently got caught in some fishing line but was rescued by the collective efforts of the good people who live in my community. Returning last night and again this morning and afternoon (where I arrived just in time for the first feed I've ever seen), I picked up my good camera for the first time a long time. With the preponderance of excellent birds in my neighborhood - since working from home, I've seen cardinals and blue jays; a tufted titmouse, a blue-grey gnatcatcher; a nuthatch; robins, starlings, and swifts; and was serenaded this past weekend by a Carolina wren - it feels good to be looking at the world through my lens again, and in recently moving towards a substantially better life, I can start researching and saving for the longtime dream of a good telephoto lens. I'm so grateful to live here, in this place, working with incredible colleagues (despite being physically separated at the moment), and doing the work that we do. But it's also good to get out and see the bigger picture and explore my new surroundings, and so this time is also cherished as well. As of August, I'm starting a new job search spreadsheet. I've been looking for work since October 2018 (off and on - at one point, working a full time job, three part time jobs, and looking for jobs was just a bit too much). Now that my contract position has ended, I've been devoting more time to searching, as well as long discussions with people who do the kind of work I can see myself doing. I decided to do some quick data visualizations, breaking down the kind of work I've pursued in the past year: By "job," I mean anything outside of academia or outside of the museum. These include a number of academic-related jobs, such as university admin, as well as non-profits, cultural heritage orgs, publishers, etc., in addition to far-fetched jobs that have nothing to do with the academic/non-profit world. The most immediate misstep I see here is devoting more than 1/3 of my search to academic jobs last year. I don't know why I did it, particularly as most of these jobs were not in my primary field (Greek art history). There is not really much point in trying for an academic job anymore, except that it is the only world in which my education level is readily accepted. Hence the reason I gave it one more go. Second, my museum job applications also haven't panned out, but one thing I realized in the course of applying is that I've always just wanted to work in a museum. I did the PhD because that was what was required for a curatorial job, and I started it when Museum Studies Masters programs weren't so popular, so I didn't think of that as a path toward museum work. But curatorial jobs are few and far between, and other types of museum jobs (education, editorial) get hung up on my PhD, as well as my antiquities focus. I would challenge the assumption that I would leave another type of museum job for curatorial, but it's hard to convince people. I just want to work with objects and people through content creation of some sort (digital projects, writing/editing, etc.). P.S., there are no jobs in provenance research. I'm also surprised by the shift in limited term vs. non-contract jobs to which I apply. This reflects a certain amount of choose-iness, I admit. I would say that this pie chart could be flipped, for the number of contract jobs out there far exceeds those that don't have an end date. But at this stage, securing a job in which I can grow and learn is high on my list of priorities, and in my experience, limited term jobs just don't allow for this (unless they're done right). So I re-focused my search. The LT jobs on here to which I did apply are those that are most relevant to what I want to do and where I see myself and I believed they could push me in the direction of my aspirations. Finally, my rate of getting interviews appears fairly successful. 1/3 of the time is not too bad. It's also exhausting, time-consuming, and considering I am still not fully employed, ultimately discouraging. Interviews are "practice," right. But I'm ready to perform.

A couple caveats: I've not listed just how many jobs I've applied to here, nor have I listed how many just never respond, and there are lots of other small divisions that I could make. Freelance jobs are left off; most of them I haven't technically applied for. I've left off fellowships and grants (didn't get any of them this past year, and most are impossible given I was working full time until June), and I've not always been the best about keeping the spreadsheet updated (i.e, I've thrown my resume out to a few LinkedIn jobs, never heard anything, and forgot to record the application). I've also left off dozens of jobs that I ultimately gave up on applying to. So WYSIWYG. This month, August, I began a new spreadsheet. And hopefully soon, I will begin new job. I am open, flexible, adaptable. I want to be challenged, to learn, and to grow. Last weekend we headed out for a short drive to the Ballona Wetlands.It was my first trip there, although it seems I've passed it a number of times on the way down to LAX. Even in the span of an easy, short walk around the perimeter of the freshwater marsh, we were able to see a number of bird species (including a new-to-me bird, the cinnamon teal). And I got some decent camera time in with the flora: After, we headed up to the Getty Villa, where I got a penultimate stroll through the special exhibition Underworld: Imagining the Afterlife. It's only up until this Monday, March 18, so I'm glad I got to spend so much time with it. I especially enjoyed seeing some of the objects from the Walters Art Museum that were the subject of the first paper I wrote in my PhD program, including this sensitive, mournful siren:

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about diversity in cultural institutions, higher education, and digital scholarship - the three often intersecting areas in which I work. Earlier this week, I was bemoaning feeling powerless about my very data-focused and mechanical position as not really being a venue in which I could affect positive change and inclusion. How could I work towards diversity when my job is literally to edit spreadsheets of early 20th century German auction data all day? Motivated by ongoing inclusion initiatives and discussion at the ground level in my place of work in the museum field, as well as in my field of Classics, and in the digital humanities and digital scholarship, I decided to reflect on the ways in which I try to build and advocate for diversity and inclusion. All three areas are having deep and often uncomfortable conversations about how to best work collectively towards inclusion and equity. From my perspective, here are some personal small steps: In teaching:

In my post-PhD research:

“Soft skills” efforts that don’t fit into a neat box:

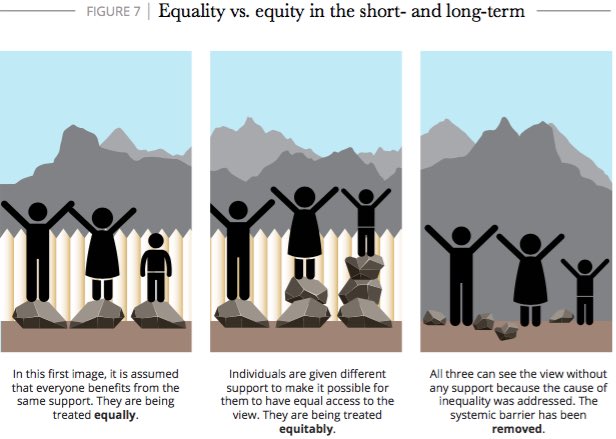

There's nothing particularly magnanimous in any of these actions, and I have so much to learn and do. Being involved in an active diversity group at my place of work has taught me to listen, to take action where I can, and to not wait around, hoping for change. We have a lot of work to do - and this list is not meant to self-congratulate myself at all, but to reflect a little in the hopes of continuing to grow and make the world even just a little bit more equitable. I was moved by this infographic that Sara Goldrick-Rab posted on twitter the other day, illustrating the differences between equality, equity, and the full removal of barriers to which we must ultimately strive: The image (the original of which was made by Craig Foehle) clarifies so well how we must all work to create equity and eventually break down systemic barriers that perpetuate inequality. Even though Dr. Goldrick-Rab used it in the context of higher education and community colleges, it’s equally applicable to so many of my own interests: museums, Classics, and the digital humanities. It is a clear image that I will keep in mind as I keep moving forward in my professional career.

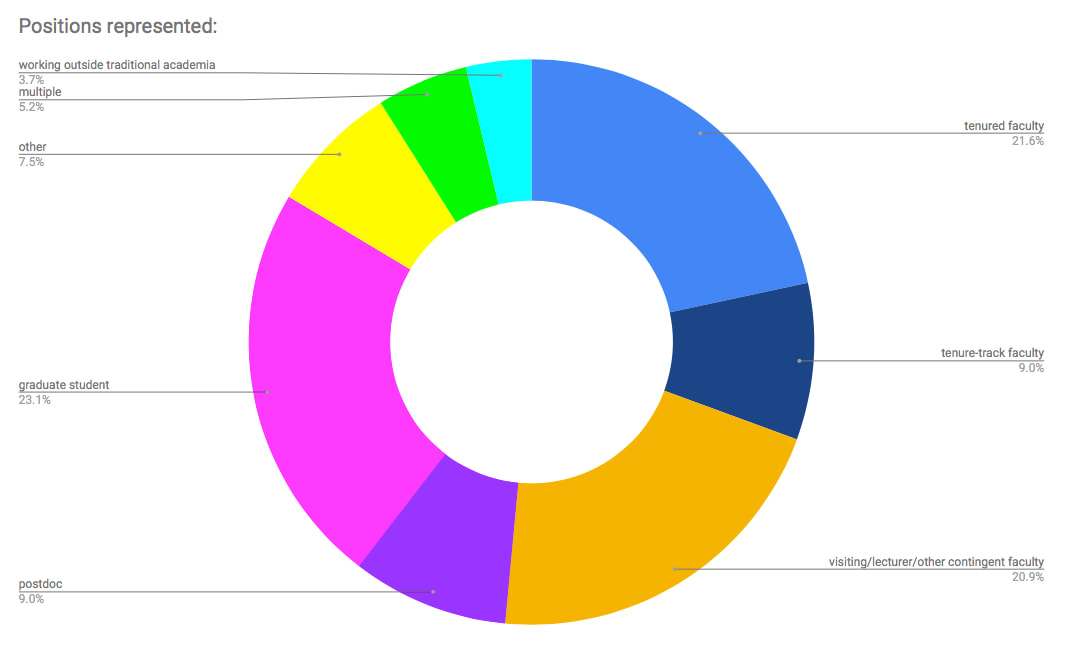

During the month of January 2019, I conducted a Google Survey of the costs of attending the Joint Annual Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America and the Society for Classical Studies. Here's the text of the survey's introduction: "What are the costs of attending our big annual conference each year? Whether it is for a job interview, presenting your current research, networking, or keeping up with the state of the fields of archaeology and Classics, the AIA/SCS is an annual tradition but can be a logistical and financial challenge for many. This survey is meant to gauge the financial costs of attending the AIA/SCS in January 2019 and who foots the bill. A rough estimate for each category is fine. Please provide amounts in your applicable currency ($, CAD, €, £, etc.). All results will remain anonymous, but feel free to contact me (Jacquelyn Clements) at jacquelynhelene@gmail.com if you have any questions. The survey will remain open until January 31, 2019." I had a remarkable 134 responses to the survey, although that's still a small percentage of attendees (maybe 5%? I will look for an official figure) - but enough to gauge a variety of responses, sources of funding, and thoughts about the acknowledged burden of what it costs to attend the meetings each year, especially whilst job hunting or building a professional network and portfolio. It will take me some time to tabulate the data. For one, I left every response field mostly open, so I have a wide range of monetary figures - some estimates, lots without currencies indicated, lots of various explanations for individual dollar amounts, etc. This is good in my opinion - it allows the survey respondent to give nuance to their answers - but it, of course, makes my job more complicated. I've therefore downloaded the survey results and made a copy of the Google Sheet that will be cleaned and standardized to format into workable and visual data. In the meantime, you might like to see a breakdown of who answered this survey: It's fairly evenly balanced, but even here, I had to make choices about the data I have at hand. The "other" category, a free form field, includes undergraduates and emerita/retired faculty, for example. I could divide this data further, but for now I'll leave it be. I also created a new category that wasn't part of the original survey, for "multiple" positions, as some people ticked more than one box (for example, I had a respondent who is both contingent faculty and works outside traditional academia). Data has the capacity for telling stories, and I hope that this survey gives an accurate but also personal picture of what the costs are of the AIA/SCS Annual Meeting - literally as well as figuratively. I look forward to working with this data more in the coming weeks, and sharing the results with you. Until then, thanks again to all who responded. As ever, if you think this work is valuable, please consider buying me a ko-fi; every little bit helps.

I keep a copy of both my CV and my resume here on my website. Why have both, when the CV is typically earmarked for academic jobs, and the resume for non-academic jobs? Here are some reasons:

I apply to both kinds of jobs Yes, that’s right, and it’s a real headache. Every cover letter is a reinvention of myself, my goals, and my experience, re-worked in ways to fit that particular position, be it a teaching job, a research job, a non-profit or philanthropy job, or a (meta)data job. In this academic climate, it’s foolish to put all of your eggs in one academic basket - unless you can afford to live off an adjunct’s salary without benefits. That was out of the question for me, so I have applied to every imaginable job in the last three years, and I needed different formats of work experience documents (i.e, the CV and resume) for different kinds of jobs. Having a current CV and a current resume at the ready makes things easier. The CV serves as a (mostly) complete record of my accomplishments This also includes the acceptances I’ve had to decline. I’m sure some people would argue that you shouldn’t list things on your CV that you’ve declined, but I’m calling for an exception. You’ve worked hard for these things; why not display the credit? In the past couple of years, I’ve had to decline some things in favor of other awards - for example, I ultimately declined a teaching fellowship that offered no pay, benefits, or security in the second semester (traditionally, this had been “gifted” as a research semester in exchange for teaching the prior semster). But even in my transition away from the traditional academic path, I’ve chosen to include two awards in 2017 on my CV because they would have been fundamental to building my scholarly output. One of them was a major fellowship to the American School. Financial restrictions prevented me from being able to accept these fellowships - should I really have to pretend the validity of my application didn’t exist as well? (That’s not to say you should include all of your “declined” things on your CV, of course, and I haven’t. I’ve been selective, and as a living document, it changes over time. Recently I read somewhere the suggestion of putting rejections and declines into a spreadsheet, which is something I’m considering.) But, the CV is unwieldy The resume is much more succinct. It’s true; the CV takes a lot longer to edit. But I try to edit both of them once every few months. Ultimately it was the resume that got me my current job, however, and you can take a look at it to see how I’ve cut to the chase in terms of the *most immediately relevant* experiences pertinent to *that particular job.* It’s hard to admit that a non-academic employer doesn’t care about your conference paper titles, but...well...they don’t. And anyone in the “extended academic” world will know the kinds of hoops you went through to get the PhD, and that might make for a nice coffee meeting, but those things are not necessary to get the job. Experience is key. The academic mantra of “one line each month” is erroneous Each line on your CV holds different weights, so passing them off as having equal value makes little sense. I also couldn’t possibly add a line for every act of service I do in this profession. For example, I spent a lot of time speaking to undergrads interested in going to graduate school, doling out information about travel in Greece, and fielding questions about images (sometimes providing those images myself, which requires hours of sifting through my personal photo archive). Should I list all of these things on my CV? I don’t, and wouldn’t know how. The argument that “this is what it takes” for a permanent job is bull. Rule #1 of academia is that there are no rules: it is a matter of chance, luck, privilege, and being in the right place at the right time (those all sound like similar things, but they aren’t, really). So, keep a master CV, or a spreadsheet, or whatever, for everything...but there’s no need to list everything for every job. Modify as needed. Cut, cut, cut (kind of like the dissertation; remember that?). How many years? We should begin thinking about graduate school as a career in and of itself, especially when systemic problems within the PhD structure can mean upwards of a decade (or more) spent in graduate school. We’re taught a lot of things one has to do in graduate school, all of which count towards building the CV. In my field, these include:

I find that's a good way of thinking about it: the resume is about what I can do. The CV is about what I have done. The division between “academia” and “alt-ac” is a fallacy I despise the term “alt-ac.” I can’t think of a single more insulting designation to the future of what PhD research can and should mean. “Look, if academia doesn’t work out, you can always do x instead.” Please. In reality, academia itself is the alt-ac. I’ll write more about this at some point. But: this goes back to my first point, that I apply to both academic and “extended academic” positions. Different jobs require different highlights, some more extensive than others. My current position was nailed down with a resume, but lately I’ve been applying for positions *outside the academy* where my CV is still more appropriate than a resume. I’m hopeful that someday that clear-cut line between “academia” and “alt-ac” (or as a colleague suggested, “extended academic”) won’t be so distinct. Until that time, we have to look at the CV and the resume both as marketable assets that highlight one’s skills and experiences, and apply specific aspects of them to our modeling of these documents. Is this helpful to you? Please consider buying me a ko-fi; every little bit helps.

A twitter thread from #aiascs Session 7I: Researching Ownership Histories for Antiquities in Museum Collections, Sunday, January 8, 2017. I blogged about the panel last year, but with the demise of Storify, I have decided to archive the tweets here:

I livetweeted this session in order to highlight some of the key points that were made during the workshop. Because each of the talks turned out to be quite captivating, I was rather minimalistic in my thoughts.

The opening remarks were given by David Saunders, Associate Curator of Antiquities at the J. Paul Getty Villa:

Next came the series of speakers, followed by an open floor discussion.

1) Paul Denis, Royal Ontario Museum, "Verifying a Provenance"

(a couple of interjections of my own thoughts)

2) Seth Pevnick, Tampa Museum of Art, "The Tampa Poseidon & The Shugborough Neptune"

3) Ann Blair Brownlee, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, "Collectors of Greek and Etruscan Vases in 19th Century Philadelphia"

The answer is no - but perhaps he was the most prolific:

4) Judith Barr, J. Paul Getty Museum, "The Pitfalls and Possibilities of Provenance Research: Historic Collections and the Art Market in the 20th Century"

5) Phoebe Segal, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, "'Said to be From': best practices for using unscientific find-spot information"

6) Amy Brauer, Harvard Art Museums, "Refining Provenance: Harvard's Road to Transparency"

7) Caroline Rocheleau, North Carolina Museum of Art, "The Stratigraphy of Provenance"

I had to duck out of the room for a few minutes, and after I returned, I was slightly distracted in trying to find the twitter handle for the North Carolina Art Museum (my bad), so I unfortunately missed a large part of Caroline's talk:

8) John Hopkins, Rice University, on the Collections Analysis Collaborative (without a powerpoint to look at, I found it a bit easier to tweet this talk):

I ended with a couple more thoughts of my own:

And this is where I stopped tweeting in order to concentrate on the open floor discussion. For more thoughts, visit my blog post about the session here.

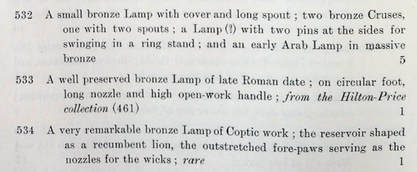

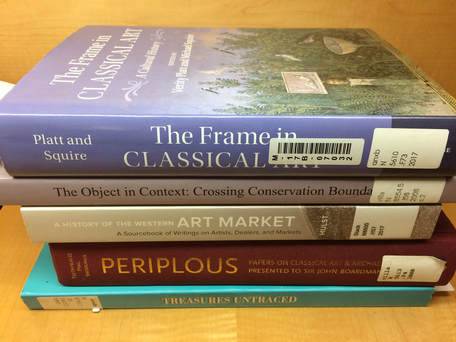

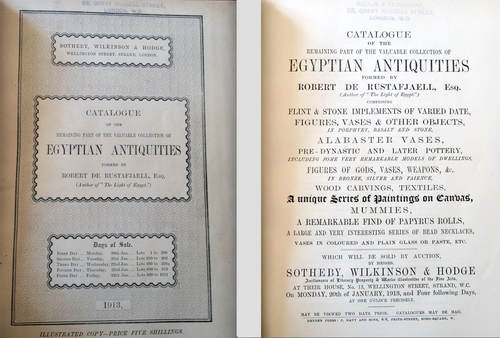

But, wait! Most of the papers from this panel have just been published, so you can now read them in full, in addition to two other panels from the AIA Toronto, all pertaining to the history of collecting and provenance of antiquities. The number of books on my bookshelf at work is quickly becoming unwieldy, so I've decided to endeavor to get through five books a week - if nothing else to browse through them and learn some new things. On the shelf this week: 1) Treasures Untraced: An Inventory of the Italian Art Treasures Lost During the Second World War (Ministero degli Affari Esteri, Rome, 1995) I actually can't remember why I requested this book. I think perhaps because I've been reading Simon Goodman's The Orpheus Clock and have become really interested in the looting of art during the Nazi occupation in World War II. There's not just Classical art in this volume listing hundreds of objects stolen during the war, but art of all time periods. Since this is an inventory of objects still missing, it would be interesting to see if this list could be shorted now that it's been twenty years since its publication. 2) Periplous: Papers on Classical Art & Archaeology Presented to Sir John Boardman (ed. G.R. Tsetskhladze et al., Thames & Hudson 2000). I've actually been long familiar with this volume of articles compiled in honor of John Boardman. On this occasion, I picked it up for a specific article, François Lissarrague's "A Sun-Struck Satyr in Malibu" (p. 190-97). I noticed this fabulous little fragment (85.AE.188) on display in the new Athenian vases gallery at the newly remodelled Getty Villa the other week. Lissarrague gave me some good chat on the inscription uttered by the masturbating satyr, which he translates to "I see two suns," and its possible meaning of "a dazzling light, a luminous phenomenon which, for the Greeks, marks an overwhelming abundance of life" (196). Isn't it a great fragment? (above) Attic red-figure kalpis fragment, attributed to the Kleophrades Painter, c. 500-480 BCE (JPGM 85.AE.188). Image courtesy of the Getty's Open Content Program. 3) The Object in Context: Crossing Conservation Boundaries (The International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works [IIC], 2006)

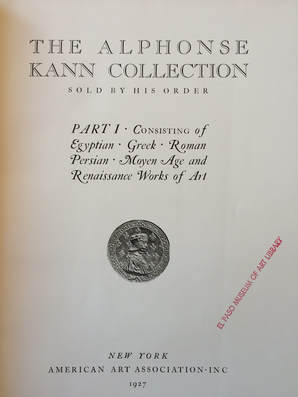

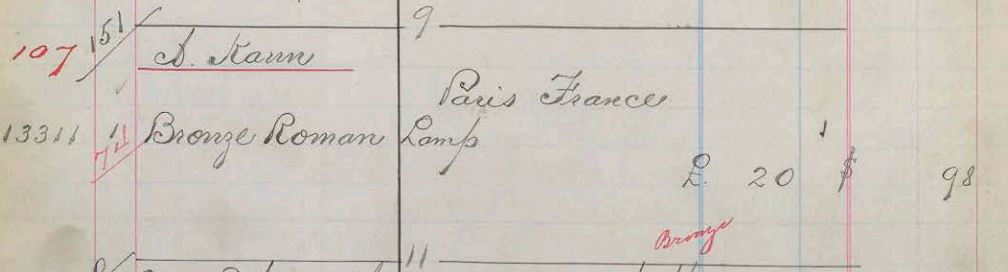

Despite being far more conservation-heavy than myself, I picked up this collection of articles from a 2006 conference in Munich for an article by Getty colleagues Erik Risser and Jens Dahener, "A Pouring Satyr from Castel Gandolfo: History and Conservation (190-96)." I've been looking at this sculpture as it's the centerpiece of a new gallery at the Getty Villa devoted to Collecting and Provenance, and I wanted to see the history of its conservation in relation to its provenance. I was then delighted to see an interesting article Jens' and Erik's, "LACMA's Classical Sculpture Collection Reconsidered - Again" (by Batyah Shtrum), that goes into the Hope and Lansdowne collections at LACMA - more provenance, and connections to the Getty, that I will eagerly explore. So I might be keeping this one for awhile. 4) A History of the Western Art Market: A Sourcebook of Writings on Artists, Dealers, and Markets (ed. T. Hulst, University of California Press, 2017) Fresh in from ILL, this volume shares snippets of many historical writings pertaining to the art market, from different times and geographical regions and a variety of perspectives amongst dealers, collectors, artists, and art historians. It looks like a rich resource, especially given its contemporary discussions. I will recommend it to collections development in the GRI; it should probably be a part of the Collecting & Provenance section of the library. 5) The Frame in Classical Art: A Cultural History (ed. V. Platt and M. Squire, Cambridge, 2017) Someone recalled this from me, so I'll need to return it before I've looked through it as in-depth as I would like. Thirteen essays - each section has its own introduction, too - explore the theme of the frame, both in two- and three-dimensional art but also in the world of texts. Not surprisingly, many of these discussions of frames are metaphorical, discussing the narrative and visual choices of ancient artists in creating their areas of focus, as well as the afterlives of display and context. It's a rich volume, no doubt, and I look forward to exploring it more (when I recall it back, ha). In last week's post, I looked at a Roman lamp in M. Knoedler's stock book that was sold to Alphonse Kann. I have a few more pieces to add to this puzzle. First, the sale of the lamp is recorded in a second Knoedler source, his sales book. I found this because the stock book provided the page number of the sales book. Here's a screen cap of Knoedler Sales Book 10, page 164 (I was able to infer the sales book number because of the year [1913]): (above) Detail of Knoedler Sales Book 10, page 164 Hurrah for more pertinent information - the "9" at the top of the page indicates the day of June that the lamp was sold. In the stock book, only the month of June had been recorded. Even better, this record gives more information about the material of the lamp - it was bronze, not the more common and expected terracotta. A bronze Roman lamp - great. What are the next steps? For one, I requested a copy of the original purchase of the lamp made by Knoedler: that from Sotheby, Wilkinson and Hodge, earlier in 1913. Lo and behold, a couple of bronze lamps are listed for sale from the Egyptian collection of Robert de Rustafjaell, Esq., British collector and fellow of the Royal Geological Society:  (above) Pages from the 1913 sale of Sotheby, Wilkinson and Hodge (right) Bronze lamps, including one from the Hilton-Price collection Is it possible that no. 533 is the bronze lamp that Knoedler bought and then sold to Alphonse Kann?  I also thought I'd check out one of the sales catalogues of Kann's collection from 1927. Alas, despite being a very attractive catalogue, I couldn't find any Roman lamps, neither listed nor photographed. Had Kann sold or given this lamp away before or after he left France for England in 1938, escaping WWII? (left) 1927 catalogue of the auction of Alphonse Kann's antiquities The final step - for now - in this little journey was to search the ERR Jeu de Paume database. This website documents the Cultural Plunder of the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR), a "Special Task Force" of Hitler that looted art objects from French and Belgian collections during WWII. Had Kann left the lamp in France when he fled his home, it may be listed in here. Indeed, there are over 1600 objects associated with Kann in the database, and well over 200 with the tag of "Antiquities." But no Roman lamp. Yet. I did, however, find an incredibly cute lamp in the shape of a mouse (?? I'm not sold on that description) from the Near East, dated to the 9th-11th cent. AD that was once part of Kann's collection [Ka 131], and with that I'll end this story - for now. The database entry includes a note that it was to be auctioned in Paris in February 2017, and one can only imaging the new travels it will have embarked on since then. The mystery of the Roman lamp bought by Knoedler and sold to Kann remains unsolved, but the journey and the pieces I've stitched together have, I hope, been at least somewhat enlightening for seeing the challenges (and rewards!) of tracing antiquities provenance. In the meantime, I'd love to hear any thoughts and comments you might have. There are so many avenues to travel in provenance research, and so much more to explore.  (right) Mouse-shaped (??) bronze oil lamp from the Near East, 9th-11th cent. AD. Formerly Alphonse Collection, Paris. ETA: For a great video and text outlining the importance of the ERR documents for the restitution of works stolen during WWII, read here. My thanks to Judith Barr and David Saunders for their helpful suggestions in researching and writing these posts. |

Author

Archives

June 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed